So here I’ve written up my thoughts and advice about how to get a postdoc and choose the right position. In my typical style, it is super long and comprehensive, but feel free to scroll down to specific sections that catch your interest.

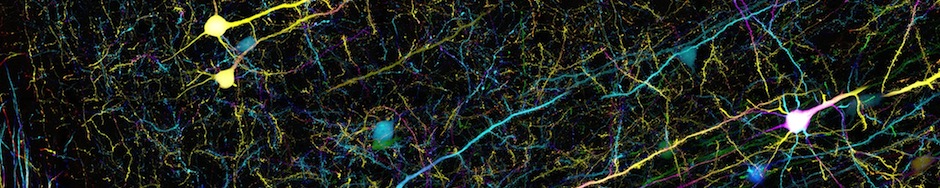

This post is based on my own experiences and those of other postdocs I know, so the usual disclaimers apply: these are my opinions and I’m sure some people will disagree; my experience is in the field of biology (specifically neuroscience) and may not be applicable to other fields.

So what’s the deal with a postdoc?

A postdoctoral position, or “postdoc”, is a position that you take after you get your PhD in order to obtain further training in your field. (Postdoc is also an abbreviation for “postdoctoral fellow” which refers to the person in that position, i.e. future you.)

Doing a postdoc is typically a similar experience to being a PhD student, except that you are more knowledgeable and experienced, and so you may be expected to be more independent. You might be expected to take on additional responsibilities like mentoring grad students or writing grants for the lab. But in general, a lot of people find the postdoc to be pretty similar to grad school.

Credit: PhD comics. Note: in my field you don’t get paid twice as much, but maybe 50% more.

You typically do a postdoc in a different lab than you did your PhD. Like most PhDs, postdocs do not have a defined time limit—you keep working until you get another job or your lab doesn’t want to fund you anymore. (Hopefully the former.) In biology, postdocs typically last from 3 to 7 years, and they seem to be getting longer—8+ years is not so unusual anymore, at least in neuroscience. Postdocs shorter than 3 years are not typical in my field but may be common in other areas.

Should I do a postdoc?

The postdoc is a necessary step if you want a tenure-track research job at a university or other research institution, such as the NIH. This kind of job is typically referred to as “staying in academia”. If you know you want one of these jobs, you need to do a postdoc. A postdoc is mainly a means to an end—the end being a tenure-track job.

If you think you might want a tenure-track research job, you should do a postdoc. It’s very hard to leave academia and then try to come back. But if you start a postdoc and decide you don’t want to stay in academia, you can always leave at any time (and you can job search during your postdoc).

If you know you don’t want an academic job, then my opinion is that there’s no reason to do a postdoc. A postdoc usually isn’t required for jobs outside of academia, such as biotech, data science, writing, policy, consulting, etc. Of course, you’ll want to talk to people in whatever industry you’re targeting to make sure this is true.

If you don’t need to do a postdoc, then I don’t recommend doing one. You don’t get paid nearly as well as you would in other jobs and the benefits usually suck. You’re in this weird limbo where you’re basically considered a glorified student (but without student benefits) even though you’re now a highly trained scientist. I’d suggest taking those skills to a proper job with stability and long-term prospects for advancement. The postdoc is temporary and you’ll need to find a “real job” eventually, so if you don’t want to stay in academia I don’t recommend spending a bunch of time in a low-paying job that doesn’t help your career.

I’m sure there are people who will disagree with me and say “even though I didn’t want to stay in academia I still really enjoyed my postdoc; I got a few years of freedom to do interesting science before working in industry”, or something like that. If you see yourself as that person, that’s fine—go ahead and do a postdoc, but just be warned that it’ll be years of being underappreciated, not earning the salary you deserve, and it probably won’t help your career (and may even hurt if you’re seen as overqualified).

Credit: PhD comics

When should I apply for postdocs?

Ok, so let’s say you’ve decided to do a postdoc. Now what?

You should start thinking about your postdoc EARLY. I recommend applying for postdocs about a year before you want to leave your PhD lab. Yes, this seems early, but the process takes time, and PIs (principal investigators, i.e. lab heads) need to plan ahead to make decisions about how much space and funding they have. If you apply too early, the worst that will happen is that they’ll say “email me again in 6 months”. But if you’re too late, they might say “I’ll have space in a year, but not earlier”.

If you’re going to apply a year in advance, then you should be thinking about potential postdocs well before that. I recommend gradually mulling things over in your head for the last couple years of grad school. Start thinking about what kind of science you want to do in the future (see below for more). Start making a list of labs you think might be a good fit. Whenever you read a paper or hear a talk that really excites you, take note of which lab it was from.

Conferences are a particularly good time to hear about a bunch of science and think about which scientific questions and approaches interest you most. They’re also a good time to see or meet potential PIs in person and get a sense of what they’re like.

How should I choose where to apply?

Now you need to decide where to apply. There are probably hundreds of labs in your general field around the world. How do you choose?

I think there are 4 main factors to consider:

- Geographical location

- Science

- PI

- lab environment

Let’s go through each of these factors individually.

1) Figure out your geographical constraints. You may be restricted in the location where you can do your postdoc (e.g. your spouse doesn’t want to leave the awesome job they already have). Or maybe you simply have strong preferences about where you want to live. You should figure this out first as it will limit your choices.

2) Think about the science. Once you’ve figured out where to look geographically, you can think about which labs are a good fit for you scientifically. This first requires some soul-searching on your part. What kind of science do you want to do? What are the major scientific questions you want to address? What systems might you want to study? What approaches do you want to take?

The research you do in your postdoc is going to be the foundation of your own lab, so you should think hard about what you want to do. Then you want to find labs that have a similar approach. They may be working on the same general questions and/or using the same methods that you’re interested in.

You do not need to find a lab that does EXACTLY what you want to do in the future. In fact, this can be a bad thing because you never want to start a lab that directly competes with your postdoc lab. Instead, just make sure that prospective labs are working on questions you find interesting, and that doing research there would set you up to do the research that you want to do in your own lab.

The postdoc is a great time to switch fields. Don’t worry too much about how you’ll lose time learning new approaches or techniques—learning new things is good! Sure, some labs only want to hire postdocs that have technical expertise in their field, but there are also plenty of labs that are open to hiring smart people and teaching them the skills they need.

Even if you don’t want to switch fields, you should try to choose a lab where you will learn something new. The whole point of a postdoc is to provide additional training, so you should take advantage of this and learn new skills that will help you in your own future lab. Don’t choose a postdoc that does exactly what your PhD lab did—you won’t learn anything.

3) Consider the PI and lab environment. My opinion is that once you’ve identified a handful of labs that you think are a good scientific fit, the PI and lab environment should be the MOST IMPORTANT factors in making your final decision. The problem is that you probably won’t know much about these factors until you visit the lab. Maybe you’ve heard rumors, and if they seem trustworthy you can factor them into your initial list of labs to apply to, but you won’t really know until you visit.

One factor you can evaluate before you visit is the reputation of the PI. Like it or not, when you apply for tenure-track jobs it’ll be easier if your PI is well-known and well-regarded in your field. This isn’t necessarily equivalent to being super famous—some famous PIs are constantly called out by their field for doing shoddy work, whereas less famous PIs might still be well-respected for their contributions to the field.

A second factor is whether the PI is new vs. well-established. Well-established PIs are less risky, because you can look at their track record to get an idea of how they run their lab and whether they’re doing good science. Well-established PIs may also be more likely to have stable funding. One thing you should do is look up their past postdocs and see what proportion of them got tenure-track jobs—this is a good metric of whether they’re doing all the things necessary to help their postdocs get jobs.

Brand new PIs are risky because you don’t have much information about whether they’ll be a good supervisor, whether they know how to get funding, etc. They don’t have a track record that you can vet. But if you visit the lab, get a very positive vibe, and feel like it’s a great fit, then it could be worth the risk.

Finally, consider the size of the lab: it might vary from 2 people to 40+ people. Postdocs can flourish in either big or small labs, but you may have a strong preference for one or the other. Maybe you really enjoyed working in a small, close-knit lab during grad school. Or maybe you enjoyed working in a large lab with a huge amount of collective expertise. People assume that a large lab means you’ll get less attention from the PI, but this isn’t always true. I know of huge labs where the PI is super involved and small labs where the PI rarely checks in.

There are many more factors regarding the PI and lab environment that you should try to find out about when you interview, but I’ll discuss them below under the “interview” section.

4) Make a list of labs to apply to. Use all the factors above to make a list of all the labs you might be interested in. Your initial list will be long. Mine was probably 30-40 labs.

To make this list, start by adding labs you’ve been thinking about over the years (based on their papers, talks, conference presentations, etc). Then browse the websites of departments that have a good reputation in your field and are based in the geographical areas you’re targeting. You may find labs you didn’t know existed who are doing exactly what you’re interested in.

After you’ve made this long list, narrow it down to a short list by doing more research on each lab. This should include browsing the lab’s website, reading their papers, and asking people in your lab (especially your PI) if they know anything about what these labs are like. Rank the labs in order of how interested you are. Keep in mind that lab websites are often out of date, and even recently published papers may not reflect what the lab is currently doing. Don’t eliminate labs that aren’t doing exactly what you’re interested in—you may find out at an interview that their focus has changed.

You probably want to initially apply to 5-10 labs, depending on the response rate that you expect. If you’ve been super successful during grad school and/or you come from a great PhD lab/program/school, you can expect a high response rate. If you don’t get positive responses, you can always go down your list and apply to more. If you come from a lesser known lab/program/school and your CV isn’t overly impressive, you might need to cast a wider net.

Personally, I narrowed my long list of 30-40 labs down to a top 10, with a clear boundary between the top 6 (labs I was super excited about) and the next 4 (labs I was somewhat excited about). I decided to apply to the top 6 and only go to the backups if it was necessary. I got invited for interviews by 5 of the 6 labs and figured that was enough. Once you’re invited for an interview, there’s a pretty good chance you’ll get an offer.

How do I apply?

Applying for a postdoc usually means sending the PI an email. There are some PIs who post more specific instructions on their lab website, which of course you should follow. If there are no instructions, then just email them.

Your email should contain a “cover letter”, which is just the body of the email. Start by introducing yourself, stating that you’re seeking a postdoc, and specifying when you expect to graduate. Write 1-2 short paragraphs describing your graduate work, then 2-3 short paragraphs explaining why you’re interested in their lab, what potential projects you could envision doing, and what skills you would contribute. Conclude by thanking them and mentioning that you’re attaching your CV, which includes references, and any other attachments you’ve included.

You’ll definitely want to attach your CV, including 3 references. If you’ve published any first-author papers in grad school, you’ll want to attach a copy of 1 or 2 of your papers. If you haven’t published yet, I think it’s ok to include a copy of a manuscript or maybe something else that demonstrates your work (e.g. poster PDF).

Make sure that your cover letter is specific to the lab your applying to! The worst thing you can do is write one generic cover letter that you send to all the labs. And when I say “specific”, I don’t just mean swap in the name of the PI and a generic description of their research from their website. You should sound passionate and convincing when describing why you’re excited about their lab and why you’d be a good fit. At the very least, you should refer to their papers. It’s even better if you can say that you attended a seminar they gave or talked to their student/postdoc at a conference.

Some people say that it’s helpful to have your PI send an email with their recommendation letter within a few days after you apply, regardless of whether you’ve gotten a response yet. Other people say to just wait for a response, especially since many PIs prefer to talk to your advisor over the phone instead of reading the letter. I imagine the letter doesn’t hurt though.

Wait up to 2 weeks for a response. If you don’t get a response by then, send a polite follow-up. If you still don’t get a response, ask your PI to send a polite follow-up. If they still don’t answer then you probably shouldn’t bother them any more.

What happens during the interview?

Hopefully you will get some responses with PIs inviting you for an interview. I also had to do one phone interview before being asked to interview in person. The in-person interviews are normally paid for by the PI (if not, this is a bad sign—either the PI has very limited funding or doesn’t care about recruiting great postdocs).

The interview usually includes the following components:

- You give a talk about your graduate work (usually 1 hour, prepare 45-50 min to leave time for questions)

- You meet with the PI

- You meet with members of the lab

- Members of the lab take you out to lunch (and sometimes dinner)

Let’s start with the talk. Your talk should be clear, rigorous, and engaging. Practice your talk many times before interviewing. Practice for your lab as well as people outside your lab (e.g. your grad school classmates). Make sure the significance of your work is clear to people outside your immediate field.

Practice answering questions, because this is a key factor when prospective PIs evaluate you. Project confidence and try not to get flustered even if you don’t know the answer. Don’t get defensive; acknowledge any legitimate caveats of your work that are raised. But stand your ground if someone is challenging you on an issue that you’re sure you’re right about.

Your meeting with the PI may take many different directions. They might want to talk about your work; they might want to talk about their work; they might want to test your knowledge of specific topics. Most likely their main goal is to get a better sense of you as a scientist and a person, and to see whether you’ll fit well within the lab.

Be prepared for questions about what kinds of scientific questions interest you and what projects you could envision carrying out in their lab. Make sure you’ve read all their recent papers and can discuss your opinions on their research. Come with questions and ideas.

Your meeting with the lab members also might take very different directions—you might talk about science, the PI, the lab, health insurance, daycare, getting around the city, etc. It’s obviously important to get a sense of what projects people are working on. But it’s even more important to use this time to get a sense of what the PI and lab environment are like.

Evaluating the PI. Let me expand on what’s important when evaluating the PI. First of all, I think that the single biggest factor that will make or break your chances for a tenure-track job is your PI. If they do not support you, it will be nearly impossible to get a job. During your postdoc, there is no graduate program to fall back on, no thesis committee to help evaluate your progress—there is only your PI. Your PI controls your fate. You need to choose someone who will support you in your quest for a tenure-track job. Remember, the postdoc is just a means to that end.

Here’s what a supportive PI looks like during a postdoc’s job search. They will advise their postdocs on applying for jobs, write a great recommendation letter, and call or email anyone they know in the departments where the postdoc is applying. They will also support all the things a postdoc needs to do in order to get to that point, including publishing papers, presenting at conferences, and applying for grants. They will create a positive relationship with their trainees and make it clear that they’re invested in their trainees’ success.

There are TONS of PIs who are not supportive in these ways. They might discourage their postdoc from applying for jobs because they want the postdoc to keep working in the lab, or they don’t want the postdoc to go set up a competing lab. They might keep insisting that the postdoc “isn’t ready” to apply for jobs even after years of experience. They might tell the postdoc that the best way to get a job is to just keep doing experiments, without allowing the postdoc any time to prepare job applications.

The PI might continually discourage or prohibit postdocs from presenting at conferences, either because they think the work isn’t good enough or because they’re paranoid about getting scooped. They might not be supportive of publishing, maybe because they think the work isn’t good enough or maybe because they’re just too lazy or disorganized to finish the paper. Even if you’re independent enough to complete a project and write a paper on your own, you need your PI to sign off on the paper before you can submit it. I know plenty of people who have to wait for years and miss one or more job application cycles for this reason alone.

And of course, the PI might be generally abusive or disrespectful of their trainees. They might mandate that everyone work 60 hour weeks or come in on the weekends. They might blame students and postdocs for experiments gone wrong. They might yell at people whenever they’re in a bad mood. Obviously none of these things are signs of a supportive relationship.

I could write many, many more pages about bad PIs (“every unhappy family is unhappy in its own way”). But you get the point: make sure that the PI supports their postdocs in all the ways that are important to ultimately get a job.

You may notice that I’ve said nothing about whether the PI actually provides mentorship and guidance throughout a postdoc’s project. This is something that obviously good PIs should do, but I don’t believe it’s essential for everyone. Some postdocs are sufficiently independent to carry out a project on their own. Others may want or need more guidance. Either way, you should make sure that the PI is at least on board with your project and trusts your data, otherwise they won’t be interested in publishing it.

So how do you find out whether the PI is supportive? Ask as many questions as you can to the people in the lab. Does the PI encourage you to go to conferences? Did they provide feedback on your grant applications? What’s it like to write a paper with them? How do they help when postdocs go on the job market? Are they a nice person? Do they make you feel guilty for taking vacations or not coming in on the weekends?

Be aware that lab members are not always honest with you—they often do not want to say anything bad about the PI. So even if they tell you things are fine, try to ask more specific questions and stay alert for any red flags. People may be more open if these conversations occur outside the lab space (e.g. at the coffee shop downstairs, or at lunch). You can also contact former postdocs in the lab for their perspective.

Evaluating the lab environment. After the PI, I think the lab environment is the second most important factor once you’ve narrowed your search down to just a few labs. If the lab is a friendly environment where people enjoy coming to work, this is a huge benefit. If the lab is a toxic environment where people hate each other or are super competitive, you’re not going to enjoy working there. You may think you can handle a toxic environment because you’re tough and focused on your work, but this isn’t something you want to do. You will be more productive if you are happy!

So ask the lab members lots of questions about what the lab is like, and also try to get a sense from observing. Do people get along? Do people seem to hang out outside of work? Do people collaborate or informally help each other? Are there conflicts in the lab? Do lab members compete with one another? What is the overall vibe like (professional, friendly, competitive, standoffish, isolated)?

Again, people may not be completely honest if there are problems in the lab, so you’ll have to read between the lines. In my interviews, it was very obvious when a lab had a great environment because people seemed so friendly and sociable, especially when they took me to lunch and I could see them hang out as a group. It was a bit more difficult to pick up on problematic environments because people are on their best behavior when someone is visiting.

Again, you want to ask lab members specific questions. Do you get along with your labmates? Have there been any lab conflicts? Do people help you when you need it or do they get annoyed that you’re imposing on their time?

Talk to as many people as possible in order to maximize your chances of someone being willing to talk openly. There was one lab where I talked to nearly a dozen lab members, but only one of them was willing to speak frankly about problems in the lab. If possible, have these talks outside of the lab space so they are more private.

One thing to remember is that talking to the lab members is also part of your interview. If they don’t like you, they may tell the PI. Good PIs actively solicit input about postdoc candidates from their lab members. So you can ask the lab members plenty of questions, but always be super polite and friendly!

My final advice for postdoc interviews: expect weird sh*t to happen. Here are some examples of weird stuff that happened to me or other postdocs I know:

- showing up and the PI forgot you were coming

- showing up and none of the lab members were told you were coming

- showing up and being mistaken for the new undergrad

- showing up at the specified time and place and being locked out of the lab with no one around

- emailing the PI repeatedly in the days before the interview to confirm the details and not getting any response

- being asked to wait around in the evening for the PI to come back, with no stated timeframe

- expecting to give a postdoc talk and then NOT being asked to give one

- expecting NOT to give a postdoc talk and then being asked to give one (this would be my worst nightmare!)

- being ushered out of the lab by the PI without the opportunity to talk to any lab members

- being offered beer in the middle of the day

- being interviewed by a PI who wasn’t wearing a shirt

How do I choose which lab to join?

After you interview, you will hopefully get some offers. The process of getting offers is also weird, in typical academic fashion. Some PIs will tell you in person, at the end of the interview day, that they would like to offer you a position. More commonly PIs will take a few days to think about it and solicit feedback from the lab members, then they’ll email you.

A very common experience is that the PI never tells you anything, one way or the other. Many interviews end with “let’s stay in touch” and then they never email you back. You should definitely send them a follow-up thank you email, but they may not reply to tell you whether you have an offer unless you say that you definitely want to join their lab. I think maybe they don’t want to spend energy making a decision unless you actually want to come.

Choosing where to go basically involves considering all the factors I’ve already discussed in this (very long!) post. I’ll just reiterate my opinion that once you’ve decided on a few labs that are a good scientific fit, your final decision should be based on the PI and the lab environment.

I know there are lots of people who think the lab’s science is the most important thing. It’s not. If you’re smart and capable, you’ll figure out how to do good science in any of the top few labs you’re considering. But no matter how amazing your science is, it’s nearly impossible to get a tenure-track job without a supportive PI. In my experience, unsupportive PIs and dysfunctional lab environments are the two main reasons that smart, productive postdocs who should have gotten tenure-track jobs end up quitting academia.

If you don’t feel like any of the labs you got offers from are a good fit for you, then you can apply to additional labs. Going through another cycle of interviews does take time, so hopefully you’ll figure out early that things aren’t going as well as you’d hoped and start applying to more labs as soon as you can.

Final thoughts

Here’s some final advice for transitioning into a postdoc:

It’s a great time to explore new areas, learn new skills, and meet new people.

It can be stressful. You’re under a lot of pressure to be productive within a certain amount of time. Use whatever strategies you can to manage your stress and know that we’re all in the same boat. Don’t listen to people who tell you “stop stressing, you should just be having fun!” You’re allowed to be stressed.

It can be fun. You have the freedom to work on something you’re really interested in and find new avenues of research to pursue in your future lab. Hopefully your postdoc will nurture your love for science as it makes you a better scientist.

If you have any feedback on this post or additional advice, please leave a comment below!

Thanks for the post! I’m in the penultimate year of my PhD (also in neuroscience). Couple of questions:

1. If I interview ~1 year before starting the postdoc, and the interview goes well, then how does the hiring process work? Is the position promised to me with a tentative start date?

2. Suppose my PhD takes a little longer than expected. Can I expect the PI to be cool with this? Would this jeopardize the postdoc position?

These are things to discuss with the PI either when you interview or when they give you an offer. Yes, they promise you the position with a tentative start date– it’s usually not set in stone. It’s pretty common for it to be pushed back if your PhD takes a little longer (I delayed mine by 3 months), and usually the PI is ok with it. But yeah, definitely try to find out how flexible they are before you commit to them.

Amazing post as usual Anita! Wish this had been in existence while I was trying to figure out how to do this whole postdoc thing. The piece of advice that I would give is that if you are hoping to find an academic position after your postdoc, it’s important to think about how you’re going to sell yourself after your postdoc ahead of time. Anita mentioned this and I wanted to emphasize it based on my experience. If there’s any way you can find a lab that will give you some unique set of training when combined with your phd lab training and/or make you particularly desirable to academic departments looking to hire faculty in the future that’s extremely helpful. For example, if you’re a neuroscientist you may even want to consider labs that are outside of traditional neuroscience departments if they can give you a unique skill set or area of expertise that you can combine with your background in neuroscience. That way, when you go on the job market after your postdoc, you’ll be able to sell yourself as bringing something to a department that they don’t already have which will make you a much stronger candidate.

Great advice. And Erica’s a stud so everyone should listen to her!

Another piece of advice: also consider what kind of job you’d like after your postdoc, particularly if want you want is not a faculty position at an R1. I’m in biology education, and I’ve talked to many grad students and postdocs who are interested in teaching and in working at a teaching-focused institution but who don’t know much about breaking in to that kind of job.

It used to be that you could get a job at a SLAC (small liberal arts college) or a regional master’s-granting institution without a postdoc, but that’s not true anymore- postdocs are desirable and increasingly necessary for even to get faculty positions at these type of teaching-focused institutions. (Also, remember that there are a ton more teaching-focused institutions than large R1s, even though you may not know about them because they don’t train PhD students!) You still will be expected to carry out a research program. When you apply, the faculty at those institutions will have lots of questions about whether you can continue to carry out your research with the staff and resources available at their institution.

So, if that’s your goal, consider whether you are setting yourself up for success. On the research side, my recommendation would be to find a system that can be learned easily (you’ll be training undergrads or maybe master’s students) and that is cheap to maintain and study. In particular, avoid mammalian systems- many of these institutions don’t even have mouse facilities- and anything that involves too many pieces of expensive equipment.

On the PI side, it strongly helps to see whether the PI is supportive of people going into careers like the ones you want to go in. Many PIs have an ego about placing trainees into positions just like theirs and consider anything else as failure. You don’t want to work for them. Will the PI give you time to teach and develop undergraduate mentoring skills, or will they think you’re wasting your time? Also, you many want to consider whether the institution has good professional development programs for grad students or postdocs, such as training in science teaching. There’s a lot of research out there on how to best teach science that is NOT reflected in how many science faculty teach today.

Fantastic advice. I didn’t go into my postdoc with that mindset but am now considering SLACs / other PUIs and am super glad I happen to work in fruit flies. And being able to teach on the side has been great. People should definitely choose PIs who support their postdocs’ career development outside the lab, whether in the teaching field or otherwise.

Hey, great text :) I have a rather weird question: in case you are offered a position, but you don’t wish to accept it (either because you didn’t like the lab, or because you were offered another position, etc), what would be the best way to decline it? I had a bad experience when I was choosing my PhD lab, with a PI that got really upset (due to ‘time wasted’) when I declined his offer to go to another lab (even though he knew I was applying, as normal, to other places). I feel that this experience is now affecting my postdoc applications and I don’t apply to labs with which I’m not 99% sure I want to work with (which is very hard to know if one doesn’t know personally the PI and lab working environment).

Wow, that is really not cool on the PI’s part (and indicates you made a great decision by declining!). It’s perfectly normal to apply to many labs and turn all but 1 down! I don’t remember exactly what I wrote in my emails but I just tried to be super polite, thanked them profusely for their time, and said I hoped we would stay in touch. All of those PIs have been very nice to me whenever I’ve encountered them since then. If anyone is actually mad about this kind of thing it’s an issue with them, not you.

Dear Anita,

Fabulous summary, well written and wonderfuly direct and honest. I have been a professor for many years and try to convey these same messages to my students. Thanks for gathering and summarizing so well!

Your article is also helpful reading from the side of the PI. I will continue to do my best to avoid all the very realistic events in your “expect weird sh*t to happen” list.

Best,

Rob

I completely agree. From the PI perspective, it was thorough, thoughtful, and made me review the things I do to support my postdocs. I hope prospective postdocs see this post and read it carefully. Very valuable.

Kudos!

Hi Anita,

I’m about to apply for a postdoc. On the PI’s lab website, under “Contact Us,” it lists the email for the PI’s assistant. I can easily find the PI’s email on her faculty page, but the fact that her email is explicitly left absent on the lab website makes me believe that she wants potential lab members to contact her assistant. I was thinking of sending an email to the PI and cc’ing her assistant, but perhaps I should email just the assistant? Let me know if you have any thoughts. Thanks!

Hmm, I think it’s probably ok to email the PI if her email is easily found through an official webpage and she doesn’t explicitly say that potential lab members should contact the assistant instead. If that’s what she wanted then she could write that, so it makes me think the assistant’s info is there mainly to receive administrative requests etc. Good luck!

Hi! Great read! Thanks for the info! I have a small but specific conundrum and I’d love to year your opinion on it. I’m at the point where I’m shortlisting labs to contact, and three of my favourites are in the same department. Going by their papers, they also collaborate a lot. They work on slightly different questions, with different models systems, but on the same overall topic, which is why I’m interested in them. How do I contact these PI’s? All individually, or do I send an open email to all three? I’m thinking of sending each of them an individual email, but I guess that they’ll soon find out I contacted the others as well, and I worry that it’ll read as if I’m one of those people that contacts every single PI whose email address they stumble across.

My advice would be to contact each one individually but mention in your email that you are also contacting the other PIs too. In addition to giving them a heads up, that would give them the option of coordinating an interview if they decide to invite you.

As an aside, I had a similarly awkward situation where I was applying to two labs led by a husband and wife, but they worked on diff things at diff institutions so I felt too awkward to tell them I was applying to their spouse’s lab too. I joined one of them so it turned out ok :)

Thanks for the advice!

Hi,

Recently, I applied for a postdoc position and the PI called my reference (current supervisor) even before responding to my email. anyway! my supervisor informed me about the call and he told me that everything went well and he was so confident that I am kind of accepted and he said I should expect and email and interview from the PI applied to his lab. however, I did not receive any respone. I sent also a follow-up email to the PI, still no response. should I conclude that the PI is not interested in my application anymore? what do you think?

Ram, he’s either super-busy (not an unexpected state from a PI) or not interested. In either case, bugging him more is not going to help. If you want, go ahead and send one very polite and deferential follow-up email after the Thanksgiving holidays (assuming you’re in the US) and then let this one go. Either he’ll eventually get back to you, giving you a pleasant surprise, or he won’t and you’ll have rightfully moved on with your life and job search.

Thanks Melinda for the advice :).

I agree with Melinda. Sending multiple follow-up emails, spaced over time (and not over the holidays), is generally fine and can be the only way to remind a busy PI that you still exist. But if he hasn’t responded to 3 emails you should probably let it go– though yes, it’s still possible he will get back to you much later. PIs are not the most organized or timely of people :)

Thank you very much for your great post! I would like to have your advice… I applied for a post-doc position in a new and small lab and after the interview I was super excited for the project, however my supervisor tells me that it’s risky in terms of publications since it’s a new lab. I have a high chance of being accepted in this lab, however I started looking for other labs. If I am offered a position, is it possible to tell the PI that I am still interested in the offer, but I am looking at other possibilities and if I could have some time to decide? What would be the best way to do that and still have a chance to work in that lab if nothing else works out?

Thank you very much!

Thanks for the good advice. I am planning to do so prior to accomplished my PhD.

I recently gave a postdoc interview and it went good pi told me you are good fit and also gave me a idea about current research going on in the lab. The PI asked me for letter of recommendations so that I can procces it promptly and told on which project you would like to work.

After few days I thanked her and she replied with thank you very much for you interest in our research.

Should I wait or consider it as negative reply

If it’s ambiguous, why don’t you ask her directly whether has made a decision or when she expects to do so? There’s no point in assuming a negative decision if she hasn’t told you that! I will also say that some PIs don’t want to decide unless/until you tell them you want to join their lab. If you do, say that explicitly.

Hi Anita..Thanks for the post. I have started with my applications. However, it is just so overehelming to choose a lab. Also reading their work and align with their reasearch becomes difficult, however you do possess some skills that the lab demands. How do you go about applying to those places.? Secondly, I could see some PIs reading up the mails several times (with read receipts), however not responding to the emails. This kind of makes me confused. ARe they really interested?

Hi Anita..Thanks for the post. I have started with my applications. However, it is just so overehelming to choose a lab. Also reading their work and align with their reasearch becomes difficult, however you do possess some skills that the lab demands. How do you go about applying to those places.? Secondly, I could see some PIs reading up the mails several times (with read receipts), however not responding to the emails. This kind of makes me confused. ARe they really interested? How would I know

Hi Anita, thanks for your post. I must confess, it really help me with the basic questions am bothered with as a prospective Postdoc!

Actually, I applied for a postdoc position in a university in Norway last six months and just last month, I was interviewed for the post sought with a promise to notify me of the outcome of my application/interview/appointment within a couple of weeks.

But, what I want to find out is, are there going to be avenues or opportunities for me to ask my PI more questions about the specific roles of the post?

Thanks as I eagerly await your feedback on the issue.