We all know that Nature likes to publish sexy stories. Well, at least we scientists know. For the rest of you, Nature is one of the premier scientific journals that everyone and their mom tries to get their papers published in. The competition is brutal. Not only do you need to have a flawless story (as I’ve discussed before), it usually needs to be sexy, too.

When I say sexy I don’t mean your paper needs to be about sex. Although that certainly helps. A paper’s sex appeal refers to how interesting and click-worthy it will seem, especially to readers outside the field, which determines how much media attention it will garner for the journal. (Yeah, in some respects the top journals aren’t that different from BuzzFeed.) The sexiest papers published in the top journals are often criticized for being all style and too little substance.

This week, Nature published a new study about maternal behavior and oxytocin that has all the trappings of a typical sexy Nature paper. The study focuses on social behavior—that’s like having killer legs. It’s about oxytocin, a hormone that’s been ridiculously over-hyped in the media for its potential role in sex, love, and empathy—that’s like having perky boobs. And the paper discusses the lateralization of brain function, a popular idea referring to how the left and right sides of your brain are different—that’s like having a nice butt.

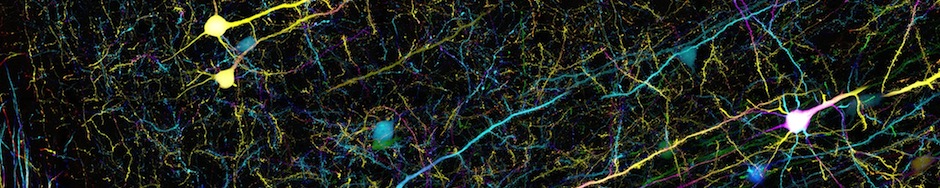

But it turns out that you can have both the looks and the brains. Despite its sex appeal, this paper describes a comprehensive and insightful set of experiments that shed light on how oxytocin shapes maternal behavior. In this study, researchers from Robert Froemke’s lab at NYU, led by grad student Bianca Jones Marlin, demonstrate that oxytocin acts in a specific, lateralized region of the brain to control how mouse mothers respond to the calls of their young pups.

Finding lost pups

If you remove mouse pups from their nest, they call for their moms. Yup, kinda like whenever parents try to get anyone else to hold their baby. Mouse mothers respond to these distress calls by locating the missing pups and dutifully bringing them back to the nest.

But this isn’t some womanly instinct that females are born with: childless female mice or brand new mothers without experience don’t know what to do. The maternal behavior develops as mothers gain experience caring for their pups. Non-mothers with pup-caring experience (i.e., mouse nannies) can also learn to respond to pup calls. Previous studies suggested that pup retrieval behavior depends on oxytocin, a hormone involved in childbirth and lactation as well as social and parental behaviors.

Lost pups emit distress calls. Experienced mothers (dams) will then retrieve them, while naive virgin females ignore the pup calls. (figure from Marlin et al., 2015)

Studies have also shown that distress calls from the pups activate neurons in a brain region called the auditory cortex, which is specialized for hearing. These auditory neurons are more strongly activated in experienced mouse mothers than in non-mothers, suggesting that different mice actually hear the same sounds differently. As a female becomes an experienced mother, her brain changes to make her more attuned to hearing her children’s cries. So it might not be that the inexperienced mothers are bad parents—it’s just that they can’t hear their pups crying.

Making mice maternal

Froemke’s group set out to investigate how oxytocin alters the auditory cortex in experienced mothers. The researchers first showed that injecting inexperienced non-mothers with oxytocin dramatically changed their behavior. Instead of ignoring the crying pups, they brought them back to the nest just like an experienced mother would. Pretty cool, right?

To understand where oxytocin might be acting in the brain, the researchers next identified which brain regions contain the receptor for oxytocin, which mediates its effect on cells. They found that oxytocin receptors were present in the auditory cortex, suggesting that it might influence how females perceive the sound of the pup calls. Surprisingly, the auditory cortex on the left side of the brain contained a lot more receptors than on the right side.

Data from Marlin et al. showing that more cells have the oxytocin receptor in the left auditory cortex compared to the right. The blue stain marks all cells; red marks cells with the receptor.

This is really unexpected because usually our brains are pretty symmetrical, despite what you may have heard in the media. Froemke’s team found that inactivating the auditory cortex on the left side, but not the right side, prevented experienced mothers from retrieving lost pups. So this really is a rare example of a behavior that’s mediated by just one half of the brain.

Hearing pup calls

The researchers then asked what oxytocin is actually doing in the left auditory cortex. They first recorded the activity of neurons in this region. In experienced mothers, pup calls robustly activated the neurons, which fired precisely timed electrical signals. In inexperienced non-mothers, however, the neurons responded more weakly and less precisely. These findings fit with previous studies suggesting that experienced mothers actually hear the pup calls more clearly than non-mothers.

The precision of neuronal responses relies on having a finely tuned balance of excitatory (positive) and inhibitory (negative) inputs to each neuron. As you might expect, the neurons in experienced mothers, but not non-mothers, showed this fine balance. Strikingly, giving oxytocin to inexperienced non-mothers improved the balance between the neurons’ positive and negative inputs, resulting in stronger and more precisely timed responses.

Data from Marlin et al. showing how excitatory and inhibitory inputs to auditory neurons are precisely correlated in experienced mothers (dams) but not naive virgins.

So now it’s finally becoming clear how oxytocin regulates pup retrieval. It doesn’t actually bestow females with motherly instincts or urge them to go looking for their pups. Instead, it simply fine-tunes the way that pup calls activate neurons in the left auditory cortex. This enables females to clearly hear their pups’ calls within the din of normal life, thus making it possible for them to locate and retrieve their kids.

Let me make sure that point is clear. At least in the case of pup retrieval, oxytocin isn’t a “love drug” or a “pleasure hormone”; it simply helps the brain learn to filter out important sensory information. And that’s still super important and interesting!

From hype to mechanism

Overall, this study represents a significant advance in our understanding of how maternal behavior develops. In contrast to most oxytocin studies that superficially link the hormone to various behaviors, this paper delves into the mechanism of how oxytocin is actually working. The authors not only show that oxytocin makes neuronal responses to pup calls stronger and more precise, they also successfully probe how these responses arise.

It’s refreshing to read a paper that transcends its sex appeal and hype. Turns out, having substance behind the looks is the sexiest thing of all.

Citation for the study:

Marlin BJ, Mitre M, D’amour JA, Chao MV, Froemke RC. Oxytocin enables maternal behaviour by balancing cortical inhibition. Nature (2015). doi:10.1038/nature14402 (advance online publication).

For other coverage of this study, also see:

News and Views by Robert Liu in Nature

Nice piece by Ed Yong in National Geographic

Interesting article. I guess most of the things are based on experience not only instinct.